Phoenix, The Brand

In the sprawling, sunbaked metropolis of Phoenix, the population swells with snowbirds during the winter—a migration that city officials encourage as enthusiastically as they woo tech leaders wearying of high prices in larger cities. Phoenix’s proponents assert that the once much-maligned city is undergoing a massive transformation—both in business growth and culture.

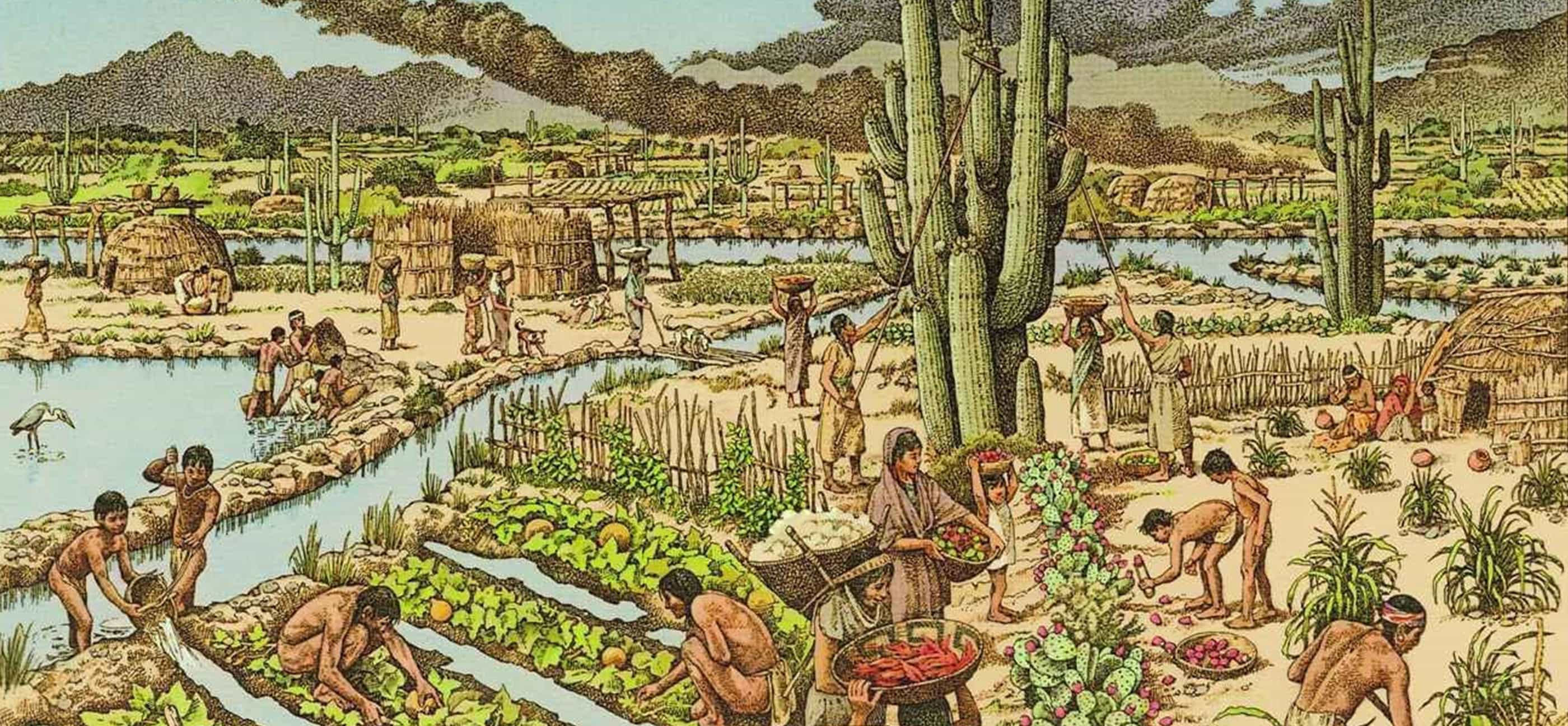

The history of Phoenix was shaped by land, drought and the ancient people and immigrants who originally settled there. As its name suggests, Phoenix sprung from the ruins of an ancient society, the first major civilization in the Salt River Valley. Between 700 A.D. and 1400 A.D., a well-established, industrious and civilized community occupied the land now known as Phoenix. These people, later dubbed by archeologists as the Hohokam (“the people who have gone”), established a vast irrigation system of 135 miles of canals (which are still in use today).

After the Hohokam vanished (likely, according to historians, due to an extended drought), the area’s history mirrors that of the larger state as a whole. Not with the traditional narrative of the lone hero taming the west, but rather through an invasion of Arizona in the 1500s by Hispanic conquistadors in search of the fabled wealth of the Seven Cities of Cibola. They were followed by traders, miners, and farmers who coexisted with the Native Americans until the 1850s, when battles between the tribes and settlers encroaching on their land led to U.S. military intervention—and the eventual confinement of tribes to reservations.

Today, the city of Phoenix, which was incorporated in 1881, is a sprawling, sunbaked metropolitan valley flanked by active Native American tribes and reservations. Often referred to as the Valley of the Sun, the city relies on a water supply sourced hundreds of miles away from the Colorado and Salt rivers. In a region that gets less than eight inches of rainfall and enjoys more than 330 days of bright sunshine a year, these lifelines give life to lush vegetation, golf courses and swimming pools that dot the landscape in squeaky clean suburbs, master-planned communities and retirement villages that sprung from virgin desert two decades ago.

Artists depiction of Hohokam tribe and irrigation canals. ©Maricopa Historical Society

Artists depiction of Hohokam tribe and irrigation canals. ©Maricopa Historical Society Snowbirds, tech transplants and real estate developers

Unlike Portland, Oregon or the Silicon Valley, (where inhabitants are nearly uniformly proud of the cities’ weirdness and rags-to-riches promise, respectively), Phoenicians often feel compelled to explain why they chose to live in a place that regularly experiences 115+ degree weather. The phrase “it’s a dry heat” is a common defense, and comparisons to the substantially higher housing costs of other major metro areas abound. Many Phoenicians are also quick to assure you that their residence is temporary, seasonal or due to a current job. They are snowbirds, retirees seeking a lower cost of living, and business owners looking for land or cost savings.

The city’s pros aren’t its’ culture, history or personality. Rather, residents boast of its low cost of living, minimal traffic and room to expand – factors that appeal to those tired of the challenges that are inherent to life and business in most major U.S. cities today. The city’s proponents also, paradoxically, tout the very same aspects the city’s detractors bemoan: namely, the weather and the lifestyle offered in the area’s numerous master-planned communities.

“When we first landed in Phoenix, we honestly couldn’t believe our luck,” said Daehee Park, the co-founder of a startup about moving his company from Silicon Valley to Phoenix. “It felt almost like we were getting away with something, like someone had forgotten to tell an entire city of people what they should be charging for the properties they were renting. Moving to Phoenix was like walking into a store you’ve been inside a lot and finding that, suddenly and unexpectedly, everything was on sale.”

Phoenix Urban Sprawl

Phoenix Urban Sprawl Transformation efforts focus on tech companies, visitors

These migration patterns are no coincidence. Phoenix officials and organizations actively target these populations: city ambassadors pitch the downtown area to young entrepreneurs “frustrated by the high cost of doing business in Silicon Valley,” according to The New York Times, while Arizona Office of Tourism officials say the agency “has worked hard to develop a strategic marketing campaign targeting key cold-weather cities in the United States and Canada.”

The campaigns aren’t limited to attracting visitors. Phoenix’s government has given developers tax breaks and other incentives to build. The state has also deliberately cultivated an environment favorable to driverless cars with a driverless car industry free of regulations; Waymo began testing driverless cars in the suburb of Chandler in late 2017 without an employee to take over the wheel in case of an emergency.

“The potential for [downtown Phoenix] is as unlimited as our sky...”

Phoenix’s proponents assert that the once much-maligned city is undergoing a transformation—in a surge of tech startups, new offices and in its culture. Visitors can float down the Salt River, see professional sports (Phoenix is home to four pro teams in the NBA, NFL, NHL and MLB) and visit the breathtaking Desert Botanical Garden. Its downtown is rebounding with new restaurants and bars, two growing state university campuses and easily walkable arts districts. The Mexico border is just four hours away by car, and Silicon Valley is 90 minutes by plane. A perceived lack of Phoenix history is a quality city leaders have more recently flipped into a positive, journalist Brenna Goth wrote recently in The Arizona Republic: Phoenix isn’t bound by tradition.

“The potential for [downtown Phoenix] is as unlimited as our sky,” proclaims Downtown Phoenix Inc., which was created to create a more vibrant community in the urban center.

Hubs of suburban life have also sprung forth from the desert in the city’s dispersed neighborhoods, each developing their own character. In the southeast suburb of Gilbert, homegrown entrepreneurs Joe and Cindy Johnston have developed a veritable enterprise of restaurants, bars and a master-planned community that captures the small-town community feel (which is lacking from most modern urban centers). Their Agritopia community, home to 400-plus houses, wraps around 12 acres of farmland that grows organic pick-your-own produce and products for their nearby locally-focused restaurants. Other neighborhoods, such as the mountain-and-canal flanked Arcadia neighborhood, or the beer-and-bike friendly Maple-Ash community, have benefited from low-cost land that’s enabled the growth of beloved spots such as La Grande Orange or Cartel Coffee.

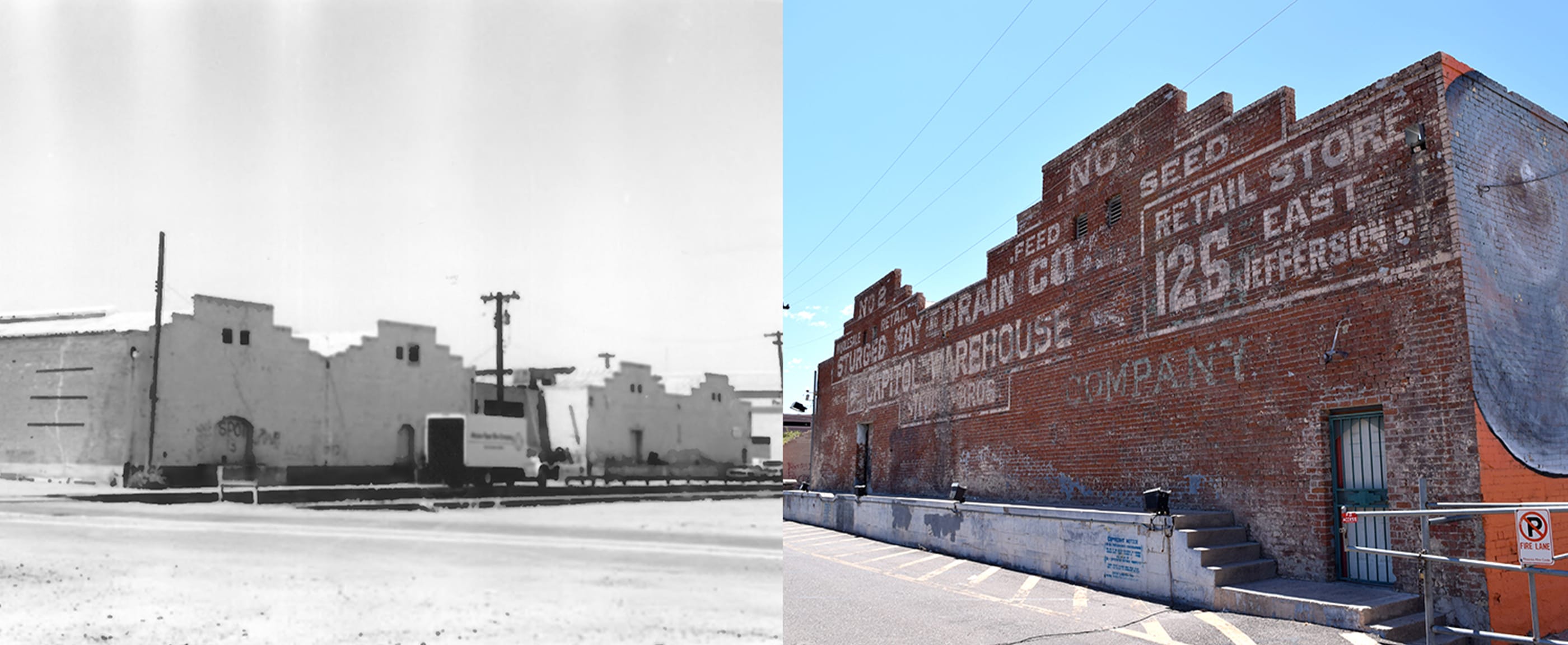

Following successful revitalizations of the urbanite neighborhoods of Roosevelt Row and Central Phoenix, a push is currently underway to transform Phoenix’s Warehouse District zone, south of downtown, into an innovation, technology and creativity hub. A coalition of local businesses and supporters meets regularly to discuss ways to brand the neighborhood, and officials are encouraging developers to salvage and remodel the area’s historic structures—a plan that’s working, The New York Times reported on March 2018, as more than 100 new businesses have moved in over the past five years.

Phoenix Seed & Feed Warehouse ©Phoenix Historic Districts Real Estate

Phoenix Seed & Feed Warehouse ©Phoenix Historic Districts Real Estate “Our goal is to keep this area gritty,” Christine Mackay, Phoenix’s director of community and economic development, told The New York Times. “It would have been far less costly to demolish all of these old buildings and start new. We want to keep the incredible fabric of the area as it has been for more than 100 years.”

As artists, creatives and business people move back into the urban core, Phoenix has a chance to position itself as something other than a stopping point for transplants or a subsidiary hub for business. The city is seizing the opportunity to develop its own culture outside the bounds of traditional “big city” norms. In doing so, it is finally embodying the spirit of its namesake.